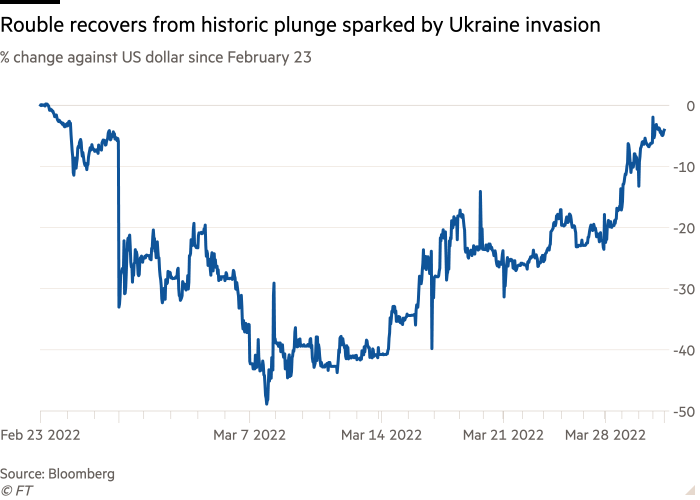

Russia’s rouble has wiped out nearly all of the losses incurred after Vladimir Putin’s invasion of Ukraine as Moscow applies draconian capital controls and blocks most foreign traders from exiting their investments.

The currency’s rebound shows how Moscow has managed to fend off a collapse of the country’s financial system, but at the cost of further isolating Russia from global finance and adding fuel to a powerful economic pullback.

In early March the rouble plunged to a 150 to the US dollar — losing almost half its value in less than a fortnight — after US and European sanctions cut Russia out of global payment systems and froze a large part of the more than $600bn war chest amassed by the country’s central bank. “As a result of our unprecedented sanctions, the rouble was almost immediately reduced to rubble,” president Joe Biden said during his visit to Poland last week.

Since then, the currency has perked up considerably, and on Thursday it traded at 81.7 to the dollar, roughly the same level as February 23, the day before Vladimir Putin sent his troops into Ukraine.

Oil and gas revenues have helped to stabilise the rouble, as exports continue flowing to Europe. But stringent curbs introduced by Moscow to prop up the rouble’s value have been crucial in staving off a deeper currency crisis, according to Oleg Vyugin, chair of the Moscow Exchange’s supervisory board and former deputy governor of the central bank.

“There was a moment in the beginning when the rouble fell sharply . . . when many citizens were moving their money abroad,” Vyugin said. “But then an embargo on this was introduced and it became pretty much impossible to use dollars in the country or abroad.”

Russians have been prohibited from moving money to their own foreign bank accounts, extracting more than $10,000 in international currencies over the next six months, or taking more than that sum out of the country in cash. Banks and brokers too have been temporarily banned from operating cash-based foreign exchanges for dollars and euros.

The central bank also more than doubled interest rates to 20 per cent, incentivising people to save their roubles rather than dump them for foreign currency. The measure prevented a run on the banks and kept the Russian banking system intact. Foreigners have also been forbidden from exiting local stocks, leaving their investments trapped.

“This is so heavily managed by the authorities that I don’t think these are levels that can be taken as a reflection of the Russian economy, or the effectiveness of sanctions,” said Cristian Maggio, head of emerging markets portfolio strategy at TD Securities.

Foreign investors, many of whom are effectively trapped holding Russian assets, are unable to transact in this market, and banks outside Russia have largely stopped quoting dollar-rouble exchange rates, according to Maggio. “Offshore this market just doesn’t exist,” he said.

Still, sanctions have actually bolstered one of the traditional strong points of Russia’s economy: its trade surplus. Soaring energy prices coupled with a sharp drop in imports has created a “very strong balance of trade, and a huge excess of currency on the trade balance,” Vyugin said.

Oil sales make up around 30 per cent of Russia’s fiscal revenues and current global price rises are “giving Russia the strongest terms of trade since ‘peak oil’ in 2008,” IIF economists Elina Ribakova and Robin Brooks added. “So even if Russia ships less oil now due to Western sanctions, Putin still gets lots of hard currency inflows.”

Ribakova forecast that Russia’s current account could probably reach $200bn to $250bn in 2022 from about $120bn in 2021 due to a collapse in imports combined with strong commodity exports. These revenues mean Russia could rebuild the central bank reserves that were frozen under sanctions in the space of just over a year, she said.

Companies that earn proceeds in foreign currencies — mainly oil and gas exporters — have also been forced to exchange 80 per cent of those proceeds into roubles, effectively outsourcing the job of supporting the currency to the private sector.

The Russian central bank spent a relatively modest $1.2bn on propping up the rouble on the two working days following the invasion, and has not intervened in currency markets since then, according to its own data. Analysts also say Putin’s plan to force European gas buyers to pay in roubles could provide a further boost to the currency.

Still, the relative strength of the currency could mask the profound damage that sanctions are expected to do to the Russian economy.

IIF’s Ribakova estimates that Russia’s economic output will shrink by 15 per cent this year, wiping out a decade and a half of growth, as domestic demand collapses — with a deeper contraction possible if there are further sanctions on oil and gas exports.

More than 400 foreign companies have withdrawn from Russia, she said, many of them “self-sanctioning” by quitting the country even if sanctions do not strictly require them to do so.

“The exchange rate is part of a political effort to imply the sanctions aren’t working,” said Timothy Ash, an economist at BlueBay Asset Management. “But it’s not a real market. And wherever the rouble is trading today, tomorrow, or next year, Putin has turned Russia into an international pariah.”